Linda Nordling | SCIENCE

Although Africa reported its millionth official COVID-19 case last week, it seems to have weathered the pandemic relatively well so far, with fewer than one confirmed case for every thousand people and just 23,000 deaths so far. Yet several antibody surveys suggest far more Africans have been infected with the coronavirus—a discrepancy that is puzzling scientists around the continent. “We do not have an answer,” says immunologist Sophie Uyoga at the Kenya Medical Research Institute–Wellcome Trust Research Programme.

After testing more than 3000 blood donors, Uyoga and colleagues estimated in a preprint last month that one in 20 Kenyans aged 15 to 64—or 1.6 million people—has antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, an indication of past infection. That would put Kenya on a par with Spain in mid-May when that country was descending from its coronavirus peak and had 27,000 official COVID-19 deaths. Kenya’s official toll stood at 100 when the study ended. And Kenya’s hospitals are not reporting huge numbers of people with COVID-19 symptoms.

Other antibody studies in Africa have yielded similarly surprising findings. From a survey of 500 asymptomatic health care workers in Blantyre, Malawi, immunologist Kondwani Jambo of the Malawi–Liverpool Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme and colleagues concluded that up to 12.3% of them had been exposed to the coronavirus. Based on those findings and mortality ratios for COVID-19 elsewhere, they estimated that the reported number of deaths in Blantyre at the time, 17, was eight times lower than expected.

Scientists who surveyed about 10,000 people in the northeastern cities of Nampula and Pemba in Mozambique found antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in 3% to 10% of participants, depending on their occupation; market vendors had the highest rates, followed by health workers. Yet in Nampula, a city of approximately 750,000, a mere 300 infections had been confirmed at the time. Mozambique only has 16 confirmed COVID-19 deaths. Yap Boum, a microbiologist and epidemiologist with Epicentre Africa, the research and training arm of Doctors Without Borders, says he found a high prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in people from Cameroon as well, a result that remains unpublished.

So what explains the huge gap between antibody data on the one hand and the official case and death counts on the other? Part of the reason may be that Africa misses many more cases than other parts of the world because it has far less testing capacity. Kenya tests about one in every 10,000 inhabitants daily for active SARS-CoV-2 infections, one-tenth of the rate in Spain or Canada. Nigeria, the continent’s most populous nation, tests one out of every 50,000 people per day. Even many people who die from COVID-19 may not get a proper diagnosis.

But in that case, you would still expect an overall rise in mortality, which Kenya has not seen, says pathologist Anne Barasa of the University of Nairobi who did not participate in the country’s coronavirus antibody study. (In South Africa, by contrast, the number of excess natural deaths reported between 6 May and 28 July exceeded its official COVID-19 death toll by a factor of four to one.) Uyoga cautions that the pandemic has hamstrung Kenya’s mortality surveillance system, however, as fieldworkers have been unable to move around.

Marina Pollán of the Carlos III Health Institute in Madrid, who led Spain’s antibody survey, says Africa’s youthfulness may protect it. Spain’s median age is 45; in Kenya and Malawi, it’s 20 and 18, respectively. Young people around the world are far less likely to get severely ill or die from the virus. And the population in Kenya’s cities, where the pandemic first took hold, skews even younger than the country as a whole, says Thumbi Mwangi, an epidemiologist at the University of Nairobi. The number of severe and fatal cases “may go higher when the disease has moved to the rural areas where we have populations with advanced age,” he says.

Jambo is exploring the hypothesis that Africans have had more exposure to other coronaviruses that cause little more than colds in humans, which may provide some defense against COVID-19. Another possibility is that regular exposure to malaria or other infectious diseases could prime the immune system to fight new pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2, Boum adds. Barasa, on the other hand, suspects genetic factors protect the Kenyan population from severe disease.

More antibody surveys may help fill out the picture. A French-funded study will test thousands for antibodies in Guinea, Senegal, Benin, Ghana, Cameroon, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo; results are expected by October. The studies will ensure good representation across populations, says Jean-François Etard from France’s Research Institute for Development, who is leading the study in Guinea jointly with a local scientist. And 13 labs in 11 African countries are participating in a global SARS-CoV-2 antibody survey coordinated by the World Health Organization.

South Africa, meanwhile, plans to conduct a number of serological studies both in COVID-19 hotspots and the general population, says Lynn Morris, who leads the country’s National Institute for Communicable Diseases. She notes that antibody prevalence found in the study will likely be an underestimate of true infection rates, given that the virus doesn’t induce antibodies in some people and that antibody levels wane over time.

If tens of millions of Africans have already been infected, that raises the question of whether the continent should try for “herd immunity” without a vaccine, Boum says—the controversial idea of letting the virus run its course to allow the population to become immune, perhaps while shielding the most vulnerable. That might be preferable over control measures that cripple economies and could harm public health more in the long run. “Maybe Africa can afford it,” given its apparent low death to infection ratio, Boum says. ”We need to dig into that.”

But Glenda Gray, president of the South African Medical Research Council, says it could be dangerous to base COVID-19 policies on antibody surveys. It’s not at all clear whether antibodies actually confer immunity, and if so, how long it lasts, Gray notes—in which case, she asks, “What do these numbers really tell us?”

MORE:

Coronavirus in South Africa: Scientists explore surprise theory for low death rate

Coronavirus: Is the rate of growth in Africa slowing down?

Scientists can’t explain puzzling lack of coronavirus outbreaks in Africa

Puzzled scientists seek reasons behind Africa's low fatality rates from pandemic

African scientists, social media users express dismay over BBC's Covid-19 article

Elizabeth Merab | NATIONAFRICA

What you need to know:

The piece elicited backlash from social media users for the better part of Thursday.

This is not the first time that scientists or journalists have expressed astonishment at Africa's low infection rates.

Africans on social media, including scientists, have expressed their disappointment over an article published by BBC Africa that explores possible theories, including poverty as a defence against coronavirus, in a bid to explain why so few Covid-19 deaths have been recorded on the continent in comparison to the rest of the world.

The piece, which posits in part that poverty may "be the the best defence against Covid-19", was published on Thursday morning.

Since Covid-19 began to spread rapidly outside China -- the initial epicentre -- to other parts of the globe, western scientists and journalists have been scrambling to explain why virus spread and deaths in Africa have remained low.

Early mathematical models had projected that the continent’s fragile health systems would be overrun and that poor living conditions would translate to high numbers of confirmed cases and deaths.

However, data shared by both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Africa Centres for Disease Control (AfricaCDC) indicate that about 1.3 million cases, 30,200 deaths, and one million recoveries have been recorded since the first case of Covid-19 was reported in Egypt in February.

In the last one week, cases have reduced by an estimated 21 percent from 52,544 to 41,614 cases. Deaths have also decreased by 13 percent from 1,562 to 1,363.

The story, which attempts to interrogate why the impact has remained low in South Africa, reads in part: “For months health experts have been warning that living conditions in poor, urban communities across Africa are likely to contribute to a rapid spread of coronavirus...What if those same crowded conditions also offer a possible solution to the mystery that has been perplexing experts on the continent for months? What if - and this is putting it rather crudely - poverty proves to be the best defence against Covid-19?”

Backlash

It quotes Professor Shabir Madhi, South Africa's top virologist, as expressing surprise that most African countries did not experience a peak like other parts of the world.

The piece elicited backlash from social media users for the better part of Thursday.

Now, some scientists have added to the criticism, noting that whereas the article itself explored credible hypotheses, the framing of the headline and “one or two sentences in the article were worrisome.”

“I disagree with the framing of the headline as well, the issue on the table is possible immune protection due to previous exposure to other coronaviruses. Unfortunately, a lot of these headlines simply push certain narratives and downplay things that we know for sure have had a big impact on how the pandemic is playing out on the continent like early, effective interventions put in place by African governments; demography, which is briefly discussed in the article etc,” said Jordan Kyongo, a Kenyan public health specialist.

Meanwhile, Executive Director of the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) Catherine Kyobutungi tweeted: “In other words there's light at the end of the tunnel - that poverty is a good thing?”

She further explained that poverty and cross-immunity from coronaviruses are not the same thing as implied in the article.

“There are many ways in which Africans socialise in large groups - markets, churches, mosques, weddings, funerals etc... Why the negative connotations that dwell on poverty? Even in good times, we can't prosper,” she said in response to a query from this writer.

“Not a scientist but it's a bit weird to frame it this way given that poverty is a clear determinant of a poor outcome in many other parts of the world,” said Linda Nordling, a science journalist and editor of Scientific African magazine.

While experts have cited Africa’s youthful population as one of the reasons for low infections and especially deaths, the fact that the continent also grapples with a myriad of communicable and non-communicable diseases like Tuberculosis, HIV, malaria, cancer, diabetes among others, was seen as a factor that would have pushed Covid-19 numbers up to exponential levels.

However, this has not been the case.

Strong reactions

This is not the first time that scientists or journalists have expressed astonishment at Africa's low infection rates.

As the virus ravaged parts of Europe months back, experts warned it was too early to celebrate that Africa had been spared the worst of it.

This was mostly due to limited testing capacity which meant that numbers at the time may have masked the true picture.

Perhaps it is this scepticism, which is seen as overlooking early mitigation efforts such as lockdowns, citizen education and aggressive screening at ports of entry, that has rubbed many Africans online the wrong way.

So when Thursday's BBC story was published, there was a flurry of bitter reactions as African journalists also expressed their disappointment with the headline.

“Could it be that “Africa’s poor” have a stronger immune system... I sarcastically ask,” Ugandan journalist Joy Doreen Biira posted.

Another Ugandan scribe, Walter Mwesigye, wrote: “Dear BBC Africa, Africa has scientists (HIGHLY QUALIFIED) just like the rest of the world who adequately advise us (natives) on the best practices. Poverty is a global challenge otherwise the poor in the United Kingdom would be non-existent by now. Shame on you!”

While responding to a tagged post by a Twitter user, former BBC Africa Business editor Larry Madowo said of the article: "...I never worked on the website though I’ve written for them. They’re fine journalists but this framing is problematic."

Author responds

In response to the online backlash today, the author of the BBC piece, Andrew Harding, said: “I'm trying to follow, and explore, the science. The experts here are confused about what's happening with Africa's pandemic. The data is emerging. Hypotheses are being tested. End of story. I'm sorry if anyone felt offended by the headline. I stand by my reporting.”

Some social media users, however, turned to humour in their reactions to the piece.

"It could also be African sorcery Mr Harding," Twitter user KyekueM quipped.

Update: Following reader concerns, BBC Africa has made some changes to the story.

“The headline and article have been updated to better reflect what the scientists said. It was not our intention to cause offence,” the news agency posted on its Twitter handle.

So... what is the one 'theory' regarding COVID deaths EVERYWHERE that just doesn't seem to get the consideration it deserves?

In one sense - and quite ironically - the authors of the BBC article may end up being right about poverty being a factor in what is helping to keep Africa's COVID mortality rate so low compared to the rest of the world... just not in the ways which they were imagining.

Of course, this is not due to all the obviously unhealthy and detestable conditions that go along with poverty - but rather, it is a 'silver lining' of it (so to speak) that most poor people outside of Western countries cannot afford or do not even have ready access to the same variety or amount of 'rich', toxic foods.

For starters in this context, all one needs to do is study up a bit on the subjects of sugar -- most especially the highly refined sort, carbohydrates in high-glycemic processed foods and alcoholic beverages -- as well as their extremely deleterious effects the immune system.

READ MORE:

Alcohol Consumption • OUR WORLD IN DATA

Leading countries in consumption of alcoholic beverages worldwide in 2018 (in billion liters)*

Differences in alcohol consumption and drinking patterns in Ghanaians in Europe and Africa: The RODAM Study

But be ye warned, ye people who wish to continue to walk in darkness and come now to see a great light... for history has shown that after a drunken nation does much feasting, it is often followed by the harsh consequences of famine and bloodshed...

African scientists, social media users express dismay over BBC's Covid-19 article

Elizabeth Merab | NATIONAFRICA

What you need to know:

The piece elicited backlash from social media users for the better part of Thursday.

This is not the first time that scientists or journalists have expressed astonishment at Africa's low infection rates.

Africans on social media, including scientists, have expressed their disappointment over an article published by BBC Africa that explores possible theories, including poverty as a defence against coronavirus, in a bid to explain why so few Covid-19 deaths have been recorded on the continent in comparison to the rest of the world.

The piece, which posits in part that poverty may "be the the best defence against Covid-19", was published on Thursday morning.

Since Covid-19 began to spread rapidly outside China -- the initial epicentre -- to other parts of the globe, western scientists and journalists have been scrambling to explain why virus spread and deaths in Africa have remained low.

Early mathematical models had projected that the continent’s fragile health systems would be overrun and that poor living conditions would translate to high numbers of confirmed cases and deaths.

However, data shared by both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Africa Centres for Disease Control (AfricaCDC) indicate that about 1.3 million cases, 30,200 deaths, and one million recoveries have been recorded since the first case of Covid-19 was reported in Egypt in February.

In the last one week, cases have reduced by an estimated 21 percent from 52,544 to 41,614 cases. Deaths have also decreased by 13 percent from 1,562 to 1,363.

The story, which attempts to interrogate why the impact has remained low in South Africa, reads in part: “For months health experts have been warning that living conditions in poor, urban communities across Africa are likely to contribute to a rapid spread of coronavirus...What if those same crowded conditions also offer a possible solution to the mystery that has been perplexing experts on the continent for months? What if - and this is putting it rather crudely - poverty proves to be the best defence against Covid-19?”

Backlash

It quotes Professor Shabir Madhi, South Africa's top virologist, as expressing surprise that most African countries did not experience a peak like other parts of the world.

The piece elicited backlash from social media users for the better part of Thursday.

Now, some scientists have added to the criticism, noting that whereas the article itself explored credible hypotheses, the framing of the headline and “one or two sentences in the article were worrisome.”

“I disagree with the framing of the headline as well, the issue on the table is possible immune protection due to previous exposure to other coronaviruses. Unfortunately, a lot of these headlines simply push certain narratives and downplay things that we know for sure have had a big impact on how the pandemic is playing out on the continent like early, effective interventions put in place by African governments; demography, which is briefly discussed in the article etc,” said Jordan Kyongo, a Kenyan public health specialist.

Meanwhile, Executive Director of the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) Catherine Kyobutungi tweeted: “In other words there's light at the end of the tunnel - that poverty is a good thing?”

She further explained that poverty and cross-immunity from coronaviruses are not the same thing as implied in the article.

“There are many ways in which Africans socialise in large groups - markets, churches, mosques, weddings, funerals etc... Why the negative connotations that dwell on poverty? Even in good times, we can't prosper,” she said in response to a query from this writer.

“Not a scientist but it's a bit weird to frame it this way given that poverty is a clear determinant of a poor outcome in many other parts of the world,” said Linda Nordling, a science journalist and editor of Scientific African magazine.

While experts have cited Africa’s youthful population as one of the reasons for low infections and especially deaths, the fact that the continent also grapples with a myriad of communicable and non-communicable diseases like Tuberculosis, HIV, malaria, cancer, diabetes among others, was seen as a factor that would have pushed Covid-19 numbers up to exponential levels.

However, this has not been the case.

Strong reactions

This is not the first time that scientists or journalists have expressed astonishment at Africa's low infection rates.

As the virus ravaged parts of Europe months back, experts warned it was too early to celebrate that Africa had been spared the worst of it.

This was mostly due to limited testing capacity which meant that numbers at the time may have masked the true picture.

Perhaps it is this scepticism, which is seen as overlooking early mitigation efforts such as lockdowns, citizen education and aggressive screening at ports of entry, that has rubbed many Africans online the wrong way.

So when Thursday's BBC story was published, there was a flurry of bitter reactions as African journalists also expressed their disappointment with the headline.

“Could it be that “Africa’s poor” have a stronger immune system... I sarcastically ask,” Ugandan journalist Joy Doreen Biira posted.

Another Ugandan scribe, Walter Mwesigye, wrote: “Dear BBC Africa, Africa has scientists (HIGHLY QUALIFIED) just like the rest of the world who adequately advise us (natives) on the best practices. Poverty is a global challenge otherwise the poor in the United Kingdom would be non-existent by now. Shame on you!”

While responding to a tagged post by a Twitter user, former BBC Africa Business editor Larry Madowo said of the article: "...I never worked on the website though I’ve written for them. They’re fine journalists but this framing is problematic."

Author responds

In response to the online backlash today, the author of the BBC piece, Andrew Harding, said: “I'm trying to follow, and explore, the science. The experts here are confused about what's happening with Africa's pandemic. The data is emerging. Hypotheses are being tested. End of story. I'm sorry if anyone felt offended by the headline. I stand by my reporting.”

Some social media users, however, turned to humour in their reactions to the piece.

"It could also be African sorcery Mr Harding," Twitter user KyekueM quipped.

Update: Following reader concerns, BBC Africa has made some changes to the story.

“The headline and article have been updated to better reflect what the scientists said. It was not our intention to cause offence,” the news agency posted on its Twitter handle.

So... what is the one 'theory' regarding COVID deaths EVERYWHERE that just doesn't seem to get the consideration it deserves?

In one sense - and quite ironically - the authors of the BBC article may end up being right about poverty being a factor in what is helping to keep Africa's COVID mortality rate so low compared to the rest of the world... just not in the ways which they were imagining.

Of course, this is not due to all the obviously unhealthy and detestable conditions that go along with poverty - but rather, it is a 'silver lining' of it (so to speak) that most poor people outside of Western countries cannot afford or do not even have ready access to the same variety or amount of 'rich', toxic foods.

Doctors warn that sugar can temporarily weaken your immune system

You may have another reason to kick that soda habit for good

Mercey Livingston | CNET

Doing everything you can to keep your immune system strong can feel like a lot of work. Committing to an exercise routine, good sleep habits, taking supplements, stress management and good nutrition is no small feat, but well worth your time and effort when it comes to staying well. But what if all your valiant efforts could be undone (for about five hours) just by eating one certain food?

If your sweet tooth has emerged with a vengeance during stay-at-home orders and quarantine, then listen up: according to nutrition studies and health experts, you might want to rethink your sugar habit. "Too much sugar in your system allows the bacteria or viruses to propagate much more because your initial innate system doesn't work as well. That's why diabetics, for example, have more infections," Dr. Michael Roizen, MD and COO of the Cleveland Clinic told CNET.

How does sugar affect your immune system?

Besides being a driver behind other chronic health conditions like diabetes and heart disease, sugar consumption affects your body's ability to fight off viruses or other infections in the body. You know how your body needs certain cells to fight off infections? White blood cells, also known as "killer cells," are highly affected by sugar consumption. Like Dr. Roizen mentions, sugar hinders the immune system since, according to a study done on fruit flies, the white blood cells are not able to do their job and destroy bad bacteria or viruses as well as when someone does not eat sugar.

Another study showed that high blood sugar affects infection-fighting mechanisms in diabetics. High-sugar diets are linked to Type 2 diabetes since high sugar consumption can lead to diabetes -- a condition that in particular is associated with a higher risk of serious complications from COVID-19.

How much sugar does it take to weaken your immune response?

This nutrition study shows that it takes about 75 grams of sugar to weaken the immune system. And once the white blood cells are affected, it's thought that the immune system is lowered for about 5 hours after. This means that even someone who slept 8 hours, takes supplements and exercises can seriously damage their immune system function by drinking a few sodas or having candy or sugary desserts throughout the day.

That study above was published in the 1970s, but another study from 2011 expanded on the previous research and found that sugar, especially fructose (like the sugar in high-fructose corn syrup) negatively affected the immune response to viruses and bacteria.

Just to give you context of how 75 grams of sugar can add up:

How much sugar is considered healthy to eat in a day?

The US Office of Disease Prevention and the World Health Organization recommend that you should get no more than 10% of your daily calories from added sugar each day. Another way to look at that amount is to limit your sugar intake to no more than six teaspoons, or 25 grams total. This amount includes the sugar you may add to your coffee, the sugar in your daily chocolate serving or the hidden sugars often found in "healthy" foods like granola bars or smoothies.

Finally, if you stick to a well-balanced diet and keep your sugar consumption in check (ideally limit it to 25 grams a day), then your immune system will have a better chance to do its job and keep you from getting sick. Now is not the time to go crazy with baking desserts (no matter how much you want to perfect that cake or cookie recipe!). Enjoying them from time to time is fine, but moderation is key when it comes to staying well.

Now... all one needs to do is look at the data and observe the striking contrast in consumption of sugar by country worldwide compared to most in Africa...

Where people around the world eat the most sugar and fat

Roberto A. Ferdman | WASHINGTON POST

We all know Americans love their sugar. But data from market research firm Euromonitor suggest that the love may border on lunacy, at least compared with the rest of the world.

Here in the United States, the average person consumes more than 126 grams of sugar per day, which is slightly more than three 12-ounce cans of Coca-Cola. That's more than twice the average sugar intake of all 54 countries observed by Euromonitor. It's also more than twice what the World Health Organization recommends for daily intake, which is roughly 50 grams of sugar for someone of normal weight.

Here's the full list (notice that people eat fewer than 25 grams of sugar in only 10 countries):

Find more statistics at Statista

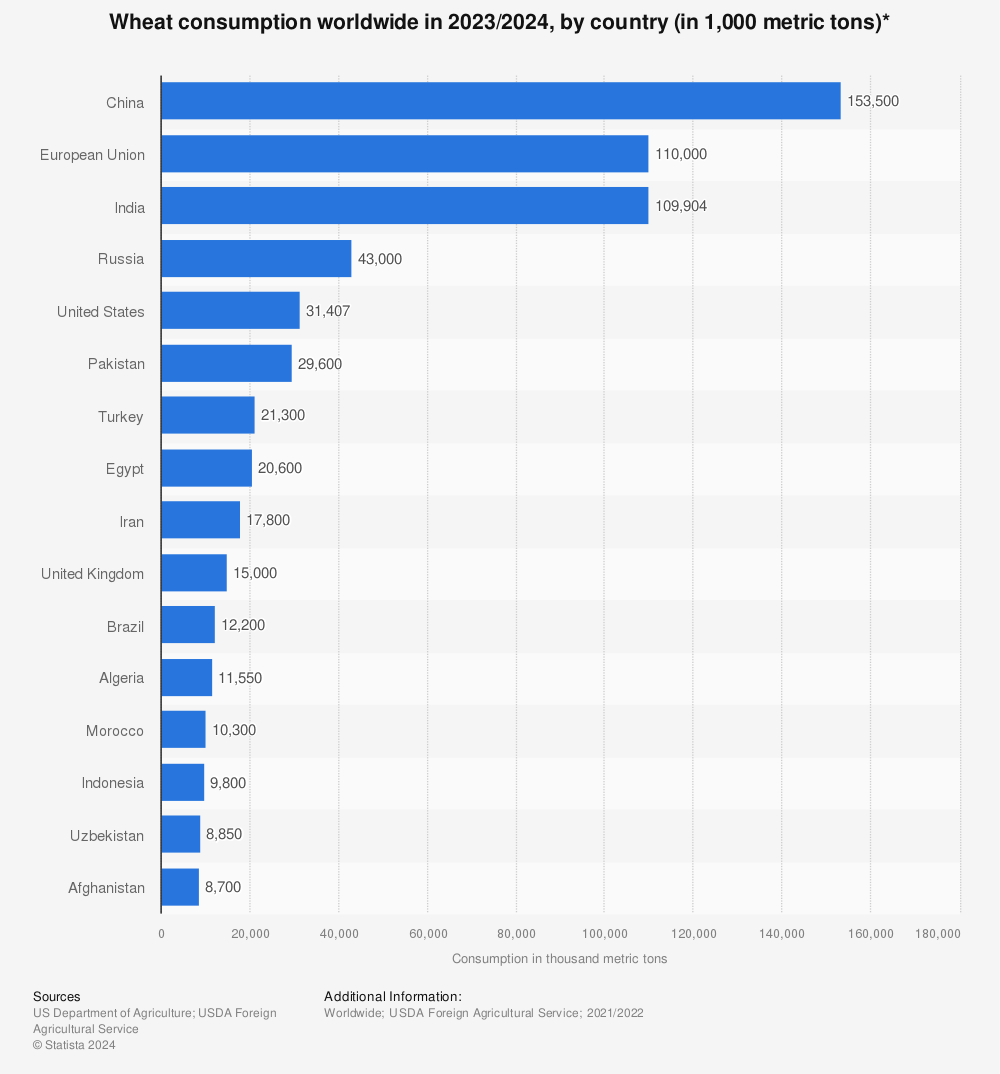

And again, keep in mind most of this wheat flour is highly refined and processed and therefore extremely toxic to the immune system... but it's not as if the Creator wanted this or hasn't warned mankind about all of these things repeatedly for a long (long!) time...

But He also gave them free will to see what they would choose to do... and in this case man decided he would rather feed himself with the worst of it...

And be assured, God most certainly knows how much man loves his CAKE... it's as if it's gone beyond 'love' and crossed over into idolatry and false worship...

You may have another reason to kick that soda habit for good

Mercey Livingston | CNET

Doing everything you can to keep your immune system strong can feel like a lot of work. Committing to an exercise routine, good sleep habits, taking supplements, stress management and good nutrition is no small feat, but well worth your time and effort when it comes to staying well. But what if all your valiant efforts could be undone (for about five hours) just by eating one certain food?

If your sweet tooth has emerged with a vengeance during stay-at-home orders and quarantine, then listen up: according to nutrition studies and health experts, you might want to rethink your sugar habit. "Too much sugar in your system allows the bacteria or viruses to propagate much more because your initial innate system doesn't work as well. That's why diabetics, for example, have more infections," Dr. Michael Roizen, MD and COO of the Cleveland Clinic told CNET.

How does sugar affect your immune system?

Besides being a driver behind other chronic health conditions like diabetes and heart disease, sugar consumption affects your body's ability to fight off viruses or other infections in the body. You know how your body needs certain cells to fight off infections? White blood cells, also known as "killer cells," are highly affected by sugar consumption. Like Dr. Roizen mentions, sugar hinders the immune system since, according to a study done on fruit flies, the white blood cells are not able to do their job and destroy bad bacteria or viruses as well as when someone does not eat sugar.

Another study showed that high blood sugar affects infection-fighting mechanisms in diabetics. High-sugar diets are linked to Type 2 diabetes since high sugar consumption can lead to diabetes -- a condition that in particular is associated with a higher risk of serious complications from COVID-19.

How much sugar does it take to weaken your immune response?

This nutrition study shows that it takes about 75 grams of sugar to weaken the immune system. And once the white blood cells are affected, it's thought that the immune system is lowered for about 5 hours after. This means that even someone who slept 8 hours, takes supplements and exercises can seriously damage their immune system function by drinking a few sodas or having candy or sugary desserts throughout the day.

That study above was published in the 1970s, but another study from 2011 expanded on the previous research and found that sugar, especially fructose (like the sugar in high-fructose corn syrup) negatively affected the immune response to viruses and bacteria.

Just to give you context of how 75 grams of sugar can add up:

- One can of soda has about 40 grams of sugar

- A low-fat, sweetened yogurt can have 47 grams of sugar

- A cupcake has about 46 grams of sugar

- Sports drinks can contain about 35 grams of sugar

How much sugar is considered healthy to eat in a day?

The US Office of Disease Prevention and the World Health Organization recommend that you should get no more than 10% of your daily calories from added sugar each day. Another way to look at that amount is to limit your sugar intake to no more than six teaspoons, or 25 grams total. This amount includes the sugar you may add to your coffee, the sugar in your daily chocolate serving or the hidden sugars often found in "healthy" foods like granola bars or smoothies.

Finally, if you stick to a well-balanced diet and keep your sugar consumption in check (ideally limit it to 25 grams a day), then your immune system will have a better chance to do its job and keep you from getting sick. Now is not the time to go crazy with baking desserts (no matter how much you want to perfect that cake or cookie recipe!). Enjoying them from time to time is fine, but moderation is key when it comes to staying well.

Now... all one needs to do is look at the data and observe the striking contrast in consumption of sugar by country worldwide compared to most in Africa...

Where people around the world eat the most sugar and fat

Roberto A. Ferdman | WASHINGTON POST

We all know Americans love their sugar. But data from market research firm Euromonitor suggest that the love may border on lunacy, at least compared with the rest of the world.

Here in the United States, the average person consumes more than 126 grams of sugar per day, which is slightly more than three 12-ounce cans of Coca-Cola. That's more than twice the average sugar intake of all 54 countries observed by Euromonitor. It's also more than twice what the World Health Organization recommends for daily intake, which is roughly 50 grams of sugar for someone of normal weight.

And it's not enough to just look at refined sugar itself.

One must also consider all the 'sugar' that adds up in the human body from the consumption of added carbohydrates in other processed and fast foods...

One of the biggest problems in Western countries like America is even most people of color love those evil 'WHITE FOODS' as much as the next person and just can't seem to keep themselves away from them - nor does it help that they are readily available 24/7 in excessive amounts.

As has been widely reported, Americans have been hit hardest by COVID - most especially 'African Americans... and with their relative rates of obesity, heart disease and diabetes being known factors as to why this is so, this may well serve as solid evidence for a large part of the reason Africans in Africa are not being affected to nearly the same extent.

And again, keep in mind most of this wheat flour is highly refined and processed and therefore extremely toxic to the immune system... but it's not as if the Creator wanted this or hasn't warned mankind about all of these things repeatedly for a long (long!) time...

But He also gave them free will to see what they would choose to do... and in this case man decided he would rather feed himself with the worst of it...

So mankind just turned their daily bread into what is basically the same thing as... cake without the frosting!

And be assured, God most certainly knows how much man loves his CAKE... it's as if it's gone beyond 'love' and crossed over into idolatry and false worship...

And lastly, let us consider wisely what's in all those aforementioned drink offerings the Lord warned us about...

READ MORE: Alcohol and Blood Sugar

All one need do is look at the relevant DATA to see what is going on with this (hint: AFRICA drinks THE LEAST!!!)...

READ MORE:

Alcohol Consumption • OUR WORLD IN DATA

Leading countries in consumption of alcoholic beverages worldwide in 2018 (in billion liters)*

Differences in alcohol consumption and drinking patterns in Ghanaians in Europe and Africa: The RODAM Study

But be ye warned, ye people who wish to continue to walk in darkness and come now to see a great light... for history has shown that after a drunken nation does much feasting, it is often followed by the harsh consequences of famine and bloodshed...

Wise UP and make the right choices regarding what you put in your body and why you are doing it! Fight your temptations and your immune system will fight for you... just like your Creator designed it to!

No comments:

Post a Comment